Nicolas Brown adapts Sean B. Carroll’s book The Serengeti Rules, at once paying homage to the five scientists at the heart of it, and explicating their theories in a handsome, engaging documentary. Like so many environmental docs that have come before it, it identifies a threat to our planet, in this case, the degradation to our natural world that ensues with the loss of biodiversity. But unlike so many films of its nature, it is more hopeful in tone. The scientists know what needs to be done to cure this particular malady; the trick is getting it done. The Serengeti Rules serves as a clarion call for action.

Nicolas Brown adapts Sean B. Carroll’s book The Serengeti Rules, at once paying homage to the five scientists at the heart of it, and explicating their theories in a handsome, engaging documentary. Like so many environmental docs that have come before it, it identifies a threat to our planet, in this case, the degradation to our natural world that ensues with the loss of biodiversity. But unlike so many films of its nature, it is more hopeful in tone. The scientists know what needs to be done to cure this particular malady; the trick is getting it done. The Serengeti Rules serves as a clarion call for action.

Working in disparate corners of the natural world—Bob Paine in the Pacific Ocean off Washington state, Jim Estes in the Aleutian Islands, Mary E. Power in the rivers and streams of Oklahoma, Tony Sinclair in Africa’s Serengeti, and John Terborgh in the Amazonian rainforest—the five scientists observed the same phenomenon: That when certain species are removed from an ecosystem, collapse follows. Paine, for example, constructed an experiment in which he removed starfish from an area of the seabed. With the predator gone, mussels proliferated while the overall diversity of species in the area dropped by half.

It was Paine who explicated the theory that the scientists ascribe to: That certain species, referred to as “keystones” and often predators, are vital to the health of communities. When they are removed from a system or die off for whatever reason, it upsets the balance and the entire system suffers.

Brown employs reenactments to illuminate his subjects’ work as young scientists. To this he adds interviews with the five, including Paine literally on his death bed, and commentary from Carroll to illustrate the keystone theory. It is not all doom and gloom. In particular, Sinclair has watched the renewal of the Serengeti after the wildebeest population rebounded with the eradication of the rinderpest disease.

The Serengeti Rules is also a spectacularly beautiful film. Tim Cragg and Simon De Glanville’s cinematography is gorgeous whether exploring the ocean floor, observing otters bobbing atop the current, following big mouth bass darting through murky water, peeking through foliage in the Amazon or Yellowstone National Park, or regarding the wildlife of the Serengeti. Those images are affirming—it really is a beautiful world we inhabit. But Brown is also making a point with such glorious depictions—it is a beautiful world and it is urgent that we pay more attention to it and the keystone species that support it. –Pam Grady

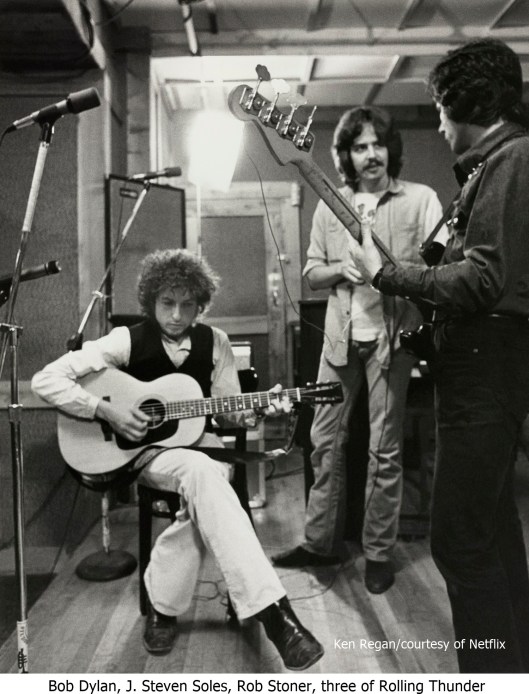

Fun fact: When Renaldo and Clara, Bob Dylan’s sole (and notoriously unsuccessful) foray into narrative filmmaking—a nearly four-hours-long fever dream combining vignettes with concert footage–opened in San Francisco in 1978, it was at the Castro Theatre. It is only fitting then that Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese that employs that same footage should have its one and only San Francisco screening before settling into its home on Netflix at the Castro. Complete with tastings of Dylan’s Heaven’s Door whiskey line, which is somehow perfect. The film, up to a point, anyway, is delicious. And so is the booze.

Fun fact: When Renaldo and Clara, Bob Dylan’s sole (and notoriously unsuccessful) foray into narrative filmmaking—a nearly four-hours-long fever dream combining vignettes with concert footage–opened in San Francisco in 1978, it was at the Castro Theatre. It is only fitting then that Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese that employs that same footage should have its one and only San Francisco screening before settling into its home on Netflix at the Castro. Complete with tastings of Dylan’s Heaven’s Door whiskey line, which is somehow perfect. The film, up to a point, anyway, is delicious. And so is the booze. Nearly 28 years ago, on Dec. 23, 1991, three little girls died in a fire in Corsicana, TX. In short order, the authorities declared the blaze an arson and identified the children’s father, Cameron Todd Willingham, a local ne’er-do-well as the killer. Fifteen years later, the state of Texas executed Willingham by lethal injection. Those are the bare bones of the case that serves as the basis for the Edward Zwick’s (Blood Diamond, Defiance) new film, Trial By Fire, a tense true-crime drama that argues that an injustice has been done and an innocent man executed. Jack O’Connell as Willingham and Laura Dern, as Elizabeth Gilbert, a playwright who worked on behalf of Willingham’s exoneration, lend their considerable talents to a riveting tale of justice denied.

Nearly 28 years ago, on Dec. 23, 1991, three little girls died in a fire in Corsicana, TX. In short order, the authorities declared the blaze an arson and identified the children’s father, Cameron Todd Willingham, a local ne’er-do-well as the killer. Fifteen years later, the state of Texas executed Willingham by lethal injection. Those are the bare bones of the case that serves as the basis for the Edward Zwick’s (Blood Diamond, Defiance) new film, Trial By Fire, a tense true-crime drama that argues that an injustice has been done and an innocent man executed. Jack O’Connell as Willingham and Laura Dern, as Elizabeth Gilbert, a playwright who worked on behalf of Willingham’s exoneration, lend their considerable talents to a riveting tale of justice denied. John Wick (Keanu Reeves) is quite the timepiece. He is the Timex watch of assassins: He’s takes a licking and keeps on ticking. In John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum he takes more licks than seems possible and still survive and even thrive, but if John Wick (it doesn’t seem right to call him either just “John”or just “Wick”) has a superpower, it is his preternatural ability to get up and keep fighting even when every fiber of his being is no doubt willing him to just stay down. John Wick is determined to live and no worldwide assassin army is going to stop him—or so he chooses to believe.

John Wick (Keanu Reeves) is quite the timepiece. He is the Timex watch of assassins: He’s takes a licking and keeps on ticking. In John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum he takes more licks than seems possible and still survive and even thrive, but if John Wick (it doesn’t seem right to call him either just “John”or just “Wick”) has a superpower, it is his preternatural ability to get up and keep fighting even when every fiber of his being is no doubt willing him to just stay down. John Wick is determined to live and no worldwide assassin army is going to stop him—or so he chooses to believe.