Tel Aviv on Fire is the name of a film. It is also the name of a soap opera within the film that has become appointment TV in Israel, Gaza, and the West Bank, set in 1967 in the months before the Six Day War and revolving around the affair between an Israeli officer and the gorgeous Palestinian spy sent to seduce him. Salam (Kais Nashif), a Palestinian who is the show’s Hebrew translator, gets bumped up to writer, a position he advances with covert help from Assi (Yaniv Biton), an Israeli border guard and superfan of the show.

Tel Aviv on Fire is the name of a film. It is also the name of a soap opera within the film that has become appointment TV in Israel, Gaza, and the West Bank, set in 1967 in the months before the Six Day War and revolving around the affair between an Israeli officer and the gorgeous Palestinian spy sent to seduce him. Salam (Kais Nashif), a Palestinian who is the show’s Hebrew translator, gets bumped up to writer, a position he advances with covert help from Assi (Yaniv Biton), an Israeli border guard and superfan of the show.

Director/co-writer Sameh Zoabi’s third narrative feature is the rare film to come at the situation between Israel and Palestine as a comedy. Zoabi himself was born in Iksal, Israel, a Palestinian village near Nazareth. Tel Aviv on Fire is a Palestinian film that is a co-production of France, Luxembourg, Belgium—and Israel. It has been nominated for four Ophirs—the Israeli equivalent of the Oscar—including Best Screenplay and Best Film. It is a film arising out of the perspective of a filmmaker who is simultaneously an insider and an outsider.

Zoabi screened Tel Aviv on Fire at the recent San Francisco Jewish Film Festival. The following day he sat down with a cinezinekane to talk about the film, using soap opera to comment on Israeli and Palestinian societies, and his unique place within those societies.

Q: Where did this story come from of this odd partnership between a Palestinian writer and an Israeli soldier?

Sameh Zoabi: The whole idea came to me, because of that personal dilemma that I lived as a Palestinian growing up inside Israel, making movies about Palestinians, and taking Israeli money to do it. So, you’re always in that dilemma with the Israelis, ‘OK, wait a second, is he a good Arab? Is he turning too Palestinian on us with his films?’ And the Arabs are like, ‘He’s taking Israeli money? Is he selling his soul to make his movies?’ Europeans always like, you know, they always want to be balanced, because they don’t want to offend anyone. But it feels like every film you make, you go through the same thing over and over. Nobody’s made a movie about this, about the politics and the people’s agenda or even if they don’t have any agenda, people’s perception of what should be and should not and what it means.

Q: From the outside, people think of Palestinians as living in Gaza or the West Bank. They don’t think about the sheer number of people that actually live and were born and have grown up within the state of Israel.

Sameh Zoabi: That was my experience when I came to Columbia University on a Fulbright scholarship. And so, it says, you know, in my files it’s always says he’s from Israel, because that’s what’s on my passport… I came to the US in 2000. People would ask, ‘Where are you from?’ ‘I am from Nazareth.’ ‘Oh, you know, we have a lot of Jewish family in Israel.’ ‘But I’m not Jewish.’ And then then you go through explaining yourself and 1948 and how we were there.

I mean I always have to justify and explain that we exist and we’ve been there and we didn’t come from anywhere else, you know what I mean? And that’s why it’s very important for me as a filmmaker to separate that. I would say that’s an important part of also moving forward is acceptance. Like Israelis, sometimes are not comfortable or, or Jewish Americans are not comfortable with the Palestinian Israeli term. Like you are a Palestinian but you are Israeli at the same time. A lot of people are like, ‘You’re an Arab Israeli.’ Yeah, but I’m Palestinian. You don’t have to run away from it by accepting it. Acknowledging the other, you can move forward. But by denying all the time that we existed to start with and even calling us something else is not going to lead us to anything.

I guess my film career has been kind of dedicated to show that side of Palestinians who live in Israel, who speak Hebrew, they can manage their way. They’re trying to survive. My first film [Man Without a Cell Phone, 2010] was also about that, about a young guy growing up in an Arab village trying to go university in Tel Aviv, like the lives that we actually live in Israel. A Palestinian who grew up in the West Bank would never be able to write or make this film, because my experience is different. I grew up knowing what Israelis think of us and what I think of them as a Palestinian. And, of course, stereotypes are the best form of comedy. It’s about how everyone sees the other.

Q: What was your thinking in setting the soap opera in 1967 before the Six Day War?

Sameh Zoabi: It’s about how everyone sees the other. So, in the West Bank they’re writing the Israeli general in ’67, imagining what the Israelis were thinking at that time. And Assi wants to change the story, because he thinks they should think otherwise. And that, for me it is always fascinating how our Palestinian experience dictates also the variety of filmmaking that we do. And we should not be judging that. In essence, we should be celebrating, you know, the different points of view. We have a narrative now where in the West Bank, Palestinians don’t meet Israelis. They only see, soldiers. In Gaza, they don’t see Israelis or soldiers. They see bombs or helicopters. For me, as a Palestinian who grew up inside, I have more possibility to interact and that’s why I was able to do this. It doesn’t mean that it’s only a film that depends on a Palestinian perspective, but it’s one that plays on this knowledge of both Palestinians and Israelis.

Q: The show isn’t just a soap opera. It’s a show everyone watches on both sides of the border.

Sameh Zoabi: That is true, by the way. When I was growing up, there were only two channels, Israeli and Jordanian. And on Fridays, every Friday, Israeli TV showed Egyptian films. And Palestinians from all over, from Gaza, the West Bank, from inside, they would all watch Egyptian films on the Israel channel and the Israelis would all watch, as well.

When I wrote the script, many people said, ‘Yeah, but that show never existed where Israelis and Palestinians both watched,’ but when I showed the film to Israelis, nobody questioned it. Because it’s not farfetched. It did happen. We had elements of it.

Q: What is this film to you?

This film captures the essence of what I’ve always believed in a sense. It’s very personal in a sense. It’s broad, it’s comedy, but it has things that Palestinians love. We just had a screening back home, in my hometown. All the Palestinian activists inside Israel wrote about how Palestinian the film is, how strong of a voice it has, how it makes fun of our reality that becomes so abnormal and tragic that we can accept the idea that someone wants to change a TV show. It’s such farfetched idea, but it’s so believable there because (of what goes on).

With Israelis, it’s the same thing. They can see through humor. I mean for me; I see Israelis and Jewish audiences responding to and following the journey of a Palestinian character and they really want him to succeed. That’s the core of it, seeing each other at this humane level. What we need is for the ground to change… We live in a reality of disconnect: Walls, checkpoints, them again us. That’s not going lead to peace, of course.

I always get a few questions about what do I think of the government? It’s like they are so busy keeping the status quo, they would do anything for people not to meet, because God forbid, if they meet they’re going to like each other. –Pam Grady

Over the course of the past seven years, Irish actress Aisling Franciosi has amassed quite a resume, counting among her characters Marie in Ken Loach’s 2014 drama Jimmy’s Hall, an award-winning turn as a serial killer-obsessed teenager in the British series The Fall (2013-2016), and Lyanna Stark, mother to Jon Snow, on Game of Thrones. In The Babadook filmmaker Jennifer Kent’s savage revenge thriller, The Nightingale, Franciosi steps into her first starring movie role. Delivering a resonant performance as Clare, a 19th-century convict of the penal colony on the Australian island of Tasmania, Franciosi convinces as a woman pushed over her limits. Forming a partnership with similarly vengeful aboriginal Billy (dancer Baykali Ganabarr in his screen debut), Clare goes on the hunt for Hawkins (Sam Claflin) and other Australian officers who have done her wrong.

Over the course of the past seven years, Irish actress Aisling Franciosi has amassed quite a resume, counting among her characters Marie in Ken Loach’s 2014 drama Jimmy’s Hall, an award-winning turn as a serial killer-obsessed teenager in the British series The Fall (2013-2016), and Lyanna Stark, mother to Jon Snow, on Game of Thrones. In The Babadook filmmaker Jennifer Kent’s savage revenge thriller, The Nightingale, Franciosi steps into her first starring movie role. Delivering a resonant performance as Clare, a 19th-century convict of the penal colony on the Australian island of Tasmania, Franciosi convinces as a woman pushed over her limits. Forming a partnership with similarly vengeful aboriginal Billy (dancer Baykali Ganabarr in his screen debut), Clare goes on the hunt for Hawkins (Sam Claflin) and other Australian officers who have done her wrong.

In a key moment of Wild Rose, aspiring country singer Rose-Lynn Harlan (Jessie Buckley) travels to London—probably the farthest she’s been outside of her hometown of Glasgow—to meet one of her heroes, real-life BBC The Country Show radio host Whispering Bob Harris—who tells her that if she is serious about making it in country music she needs to write her own songs. It is a suggestion that flummoxes her; she feels she has nothing to write about. She can’t see what the audience sees: Her life is a country song. And so is this movie, the story of a working-class heroine who can’t seem to get out of her own way, whose life would utterly defeat most other people, but whose hope and big dreams remain undistinguished.

In a key moment of Wild Rose, aspiring country singer Rose-Lynn Harlan (Jessie Buckley) travels to London—probably the farthest she’s been outside of her hometown of Glasgow—to meet one of her heroes, real-life BBC The Country Show radio host Whispering Bob Harris—who tells her that if she is serious about making it in country music she needs to write her own songs. It is a suggestion that flummoxes her; she feels she has nothing to write about. She can’t see what the audience sees: Her life is a country song. And so is this movie, the story of a working-class heroine who can’t seem to get out of her own way, whose life would utterly defeat most other people, but whose hope and big dreams remain undistinguished. Rankin-Bass probably doesn’t have cause for action, but it is impossible not to feel the influence of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer in this fourth Toy Story adventure. The world Woody (Tom Hanks) stumbles on where toys go unloved and unwanted is not an island nor toy world unto itself, but a dusty antique store where toys go unloved and unwanted. For Woody, beginning to contemplate his own obsolescence and a time when no child will call him his own, the place is a revelation. If this is truly Woody’s last roundup, he goes out in a blaze of laughter and tears.

Rankin-Bass probably doesn’t have cause for action, but it is impossible not to feel the influence of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer in this fourth Toy Story adventure. The world Woody (Tom Hanks) stumbles on where toys go unloved and unwanted is not an island nor toy world unto itself, but a dusty antique store where toys go unloved and unwanted. For Woody, beginning to contemplate his own obsolescence and a time when no child will call him his own, the place is a revelation. If this is truly Woody’s last roundup, he goes out in a blaze of laughter and tears. Nicolas Brown adapts Sean B. Carroll’s book The Serengeti Rules, at once paying homage to the five scientists at the heart of it, and explicating their theories in a handsome, engaging documentary. Like so many environmental docs that have come before it, it identifies a threat to our planet, in this case, the degradation to our natural world that ensues with the loss of biodiversity. But unlike so many films of its nature, it is more hopeful in tone. The scientists know what needs to be done to cure this particular malady; the trick is getting it done. The Serengeti Rules serves as a clarion call for action.

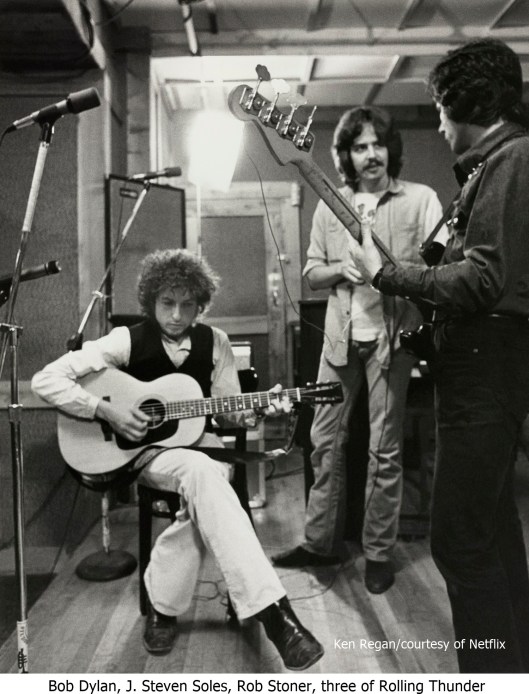

Nicolas Brown adapts Sean B. Carroll’s book The Serengeti Rules, at once paying homage to the five scientists at the heart of it, and explicating their theories in a handsome, engaging documentary. Like so many environmental docs that have come before it, it identifies a threat to our planet, in this case, the degradation to our natural world that ensues with the loss of biodiversity. But unlike so many films of its nature, it is more hopeful in tone. The scientists know what needs to be done to cure this particular malady; the trick is getting it done. The Serengeti Rules serves as a clarion call for action. Fun fact: When Renaldo and Clara, Bob Dylan’s sole (and notoriously unsuccessful) foray into narrative filmmaking—a nearly four-hours-long fever dream combining vignettes with concert footage–opened in San Francisco in 1978, it was at the Castro Theatre. It is only fitting then that Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese that employs that same footage should have its one and only San Francisco screening before settling into its home on Netflix at the Castro. Complete with tastings of Dylan’s Heaven’s Door whiskey line, which is somehow perfect. The film, up to a point, anyway, is delicious. And so is the booze.

Fun fact: When Renaldo and Clara, Bob Dylan’s sole (and notoriously unsuccessful) foray into narrative filmmaking—a nearly four-hours-long fever dream combining vignettes with concert footage–opened in San Francisco in 1978, it was at the Castro Theatre. It is only fitting then that Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese that employs that same footage should have its one and only San Francisco screening before settling into its home on Netflix at the Castro. Complete with tastings of Dylan’s Heaven’s Door whiskey line, which is somehow perfect. The film, up to a point, anyway, is delicious. And so is the booze. Anyone expecting Rocketman–a film about the life and times of Elton John, executive produced by Elton John and produced by his husband David Furnish—to be a rock star’s vanity project, will be disabused of that notion in the dramatic musical’s opening scene. That’s when Elton (Taron Egerton), arrestingly attired in a skintight, bright orange jumpsuit with feathered wings and topped off with devil horns and rhinestone, heart-shaped glasses, bursts into what is unmistakably a 12-step meeting, sits down, and confesses to a long list of addictions. No, Rocketman is not a vanity project; it’s an anti-vanity project, a lacerating portrait of the artist as a young, self-loathing man. It is a movie that defies expectations, revealing the emptiness and inner turmoil hidden beneath such a glittering career.

Anyone expecting Rocketman–a film about the life and times of Elton John, executive produced by Elton John and produced by his husband David Furnish—to be a rock star’s vanity project, will be disabused of that notion in the dramatic musical’s opening scene. That’s when Elton (Taron Egerton), arrestingly attired in a skintight, bright orange jumpsuit with feathered wings and topped off with devil horns and rhinestone, heart-shaped glasses, bursts into what is unmistakably a 12-step meeting, sits down, and confesses to a long list of addictions. No, Rocketman is not a vanity project; it’s an anti-vanity project, a lacerating portrait of the artist as a young, self-loathing man. It is a movie that defies expectations, revealing the emptiness and inner turmoil hidden beneath such a glittering career. Nearly 28 years ago, on Dec. 23, 1991, three little girls died in a fire in Corsicana, TX. In short order, the authorities declared the blaze an arson and identified the children’s father, Cameron Todd Willingham, a local ne’er-do-well as the killer. Fifteen years later, the state of Texas executed Willingham by lethal injection. Those are the bare bones of the case that serves as the basis for the Edward Zwick’s (Blood Diamond, Defiance) new film, Trial By Fire, a tense true-crime drama that argues that an injustice has been done and an innocent man executed. Jack O’Connell as Willingham and Laura Dern, as Elizabeth Gilbert, a playwright who worked on behalf of Willingham’s exoneration, lend their considerable talents to a riveting tale of justice denied.

Nearly 28 years ago, on Dec. 23, 1991, three little girls died in a fire in Corsicana, TX. In short order, the authorities declared the blaze an arson and identified the children’s father, Cameron Todd Willingham, a local ne’er-do-well as the killer. Fifteen years later, the state of Texas executed Willingham by lethal injection. Those are the bare bones of the case that serves as the basis for the Edward Zwick’s (Blood Diamond, Defiance) new film, Trial By Fire, a tense true-crime drama that argues that an injustice has been done and an innocent man executed. Jack O’Connell as Willingham and Laura Dern, as Elizabeth Gilbert, a playwright who worked on behalf of Willingham’s exoneration, lend their considerable talents to a riveting tale of justice denied.